Evolution of Recursive SNARKs

Automatically translated by AI

zkSNARK

zkSNARK is a complex Zero-Knowledge Proof system that verifies the execution of a program containing secret inputs without revealing them, proving that the program ran correctly.

The Most Widely Used SNARKs

Almost all well-known SNARKs are used in blockchain today.

Groth16 — the shortest SNARK, with proofs containing only three group elements and about 280 bytes in size.

STARK — capable of the same as Groth16 but entirely universal. Developers call it not only universal but transparent because it has no dependency on the specific circuit being proven and requires no trusted setup. It is also quantum-secure, meaning it will remain safe when quantum computers break all currently used asymmetric cryptography. When that happens, Groth16, Plonk, and Halo 2 will become obsolete.

The drawback is that STARK proofs are large. However, the advantage is very high speed, and some implementations use recursion — proving statements with STARK, then proving the STARK verifier itself with another SNARK, resulting in a compact proof of just a few kilobytes or even hundreds of bytes with Groth16.

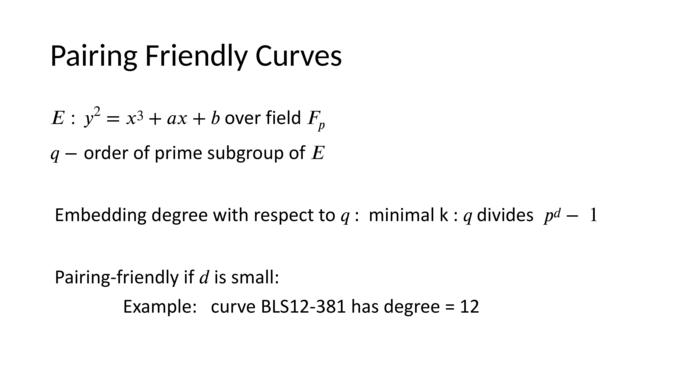

Pairing-Friendly Curves

Pairing-friendly curves have a special structure defined by the embedding degree — related not to the curve itself but to the order of the subgroup Q used by the curve. Pairing-friendly means this value is small, enabling practical computation of pairings.

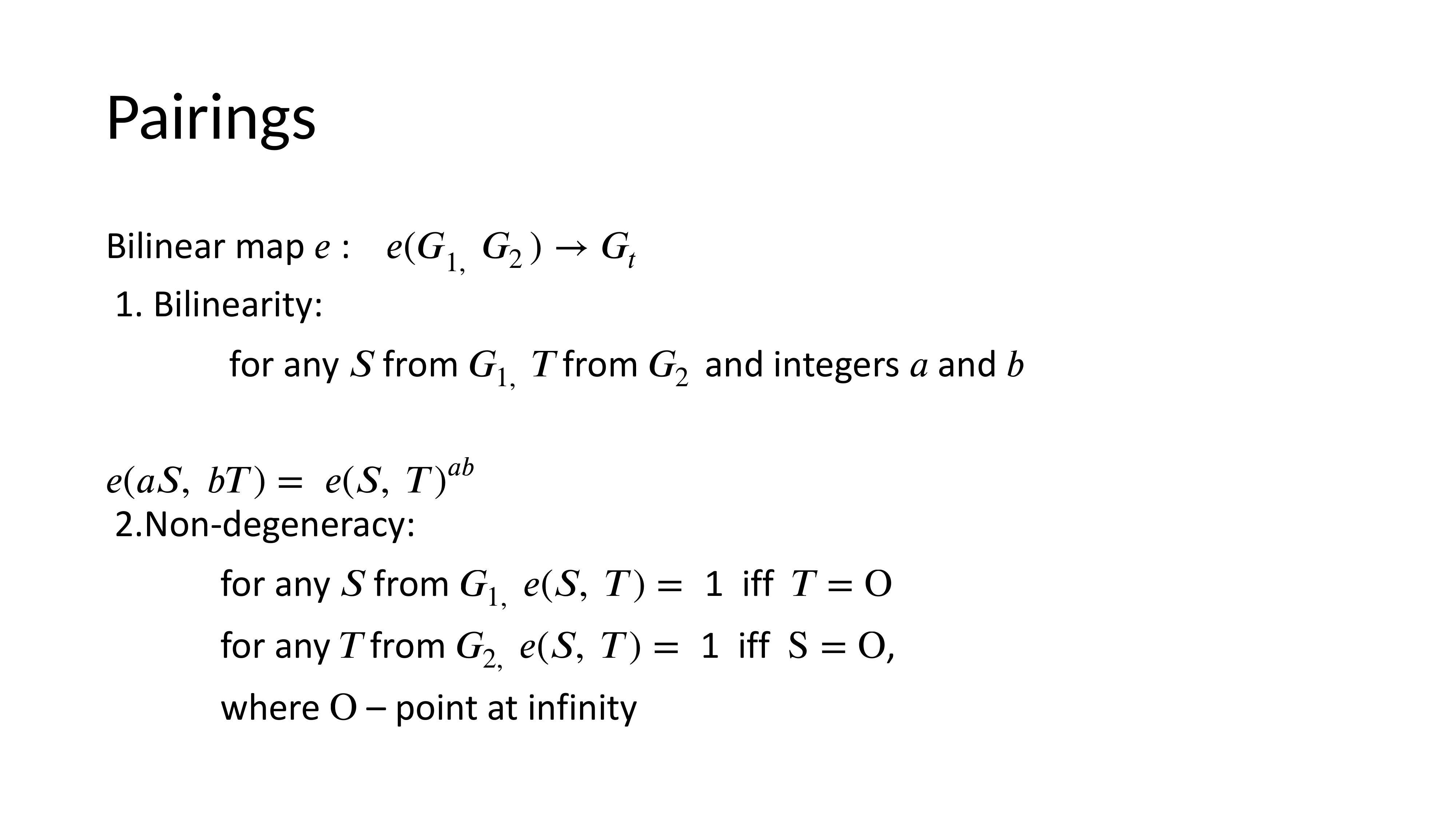

Pairings

A bilinear map satisfies: given two points from different groups G1 and G2 of order Q, computing the pairing of their scalar multiples aS and bT equals raising the pairing of S and T to the power ab.

Non-degeneracy means that if pairing(S, T) = 1 for any S, then T must be the point at infinity.

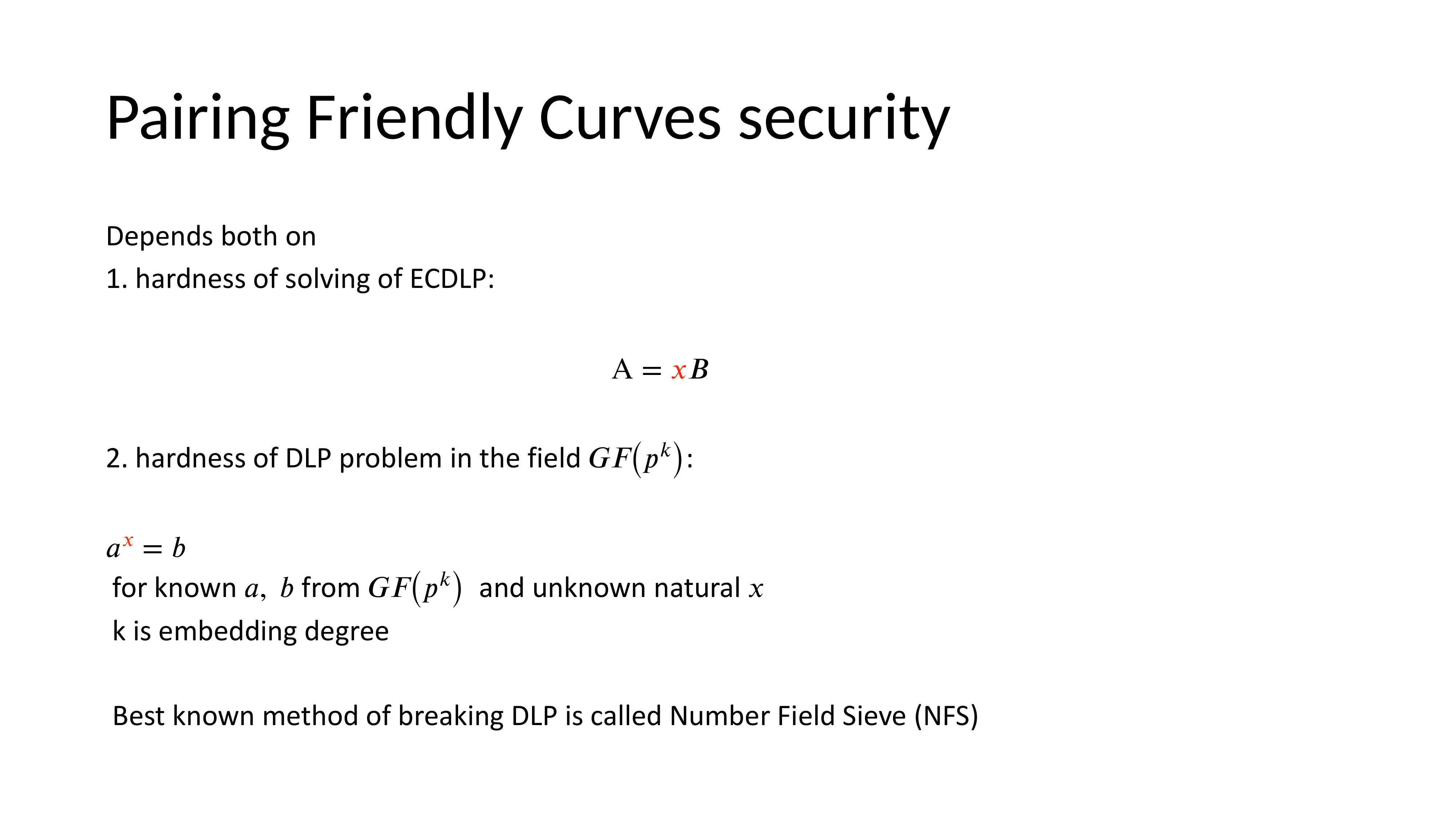

Security of Pairing-Friendly Curves

Their security relies on the discrete logarithm problem in an extension field of degree k (the embedding degree).

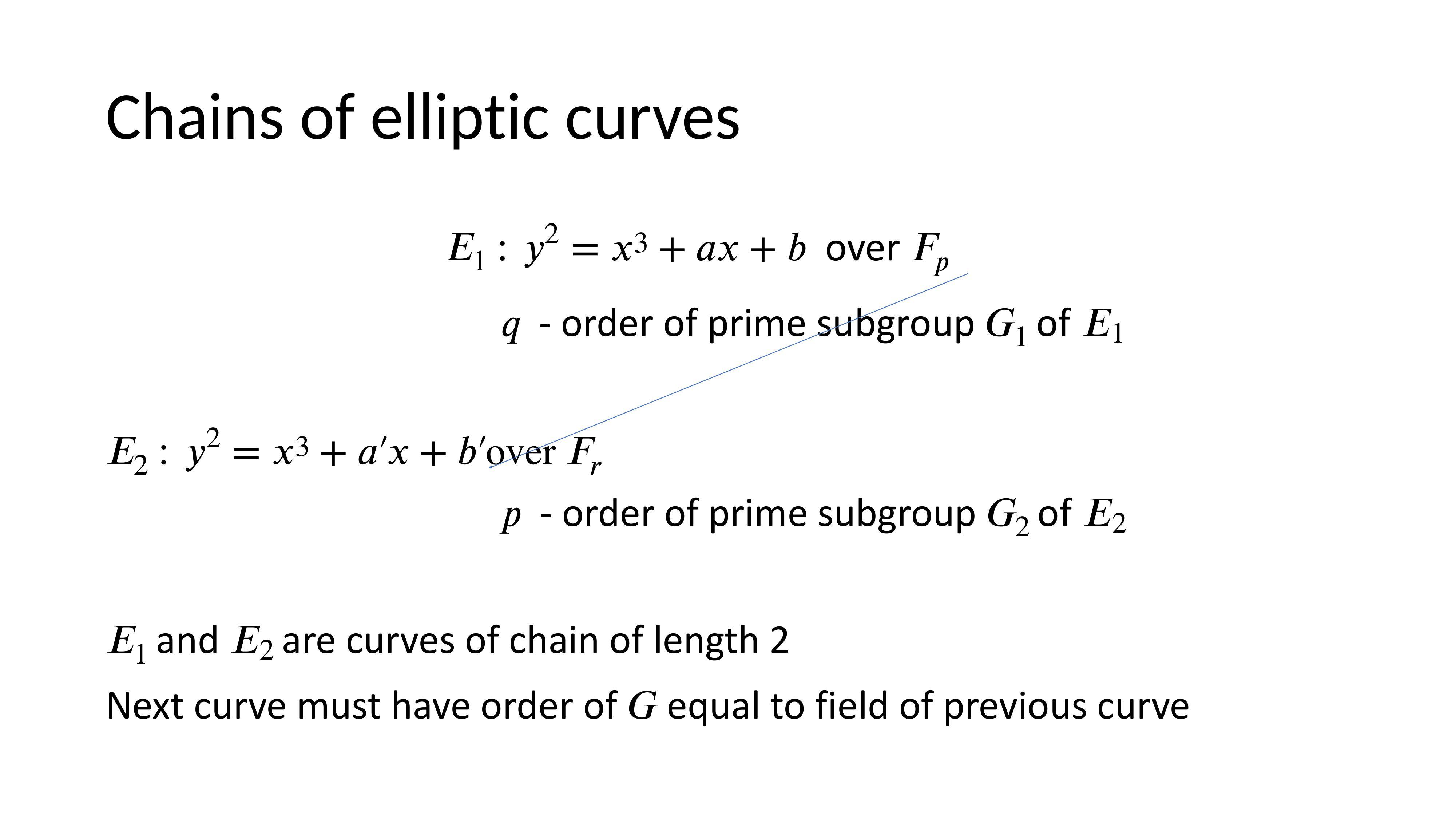

Chains of Elliptic Curves

To prove large, complex statements with SNARKs, chains of elliptic curves can be used. The circuit lies in a field equal to the scalar field of the curve. The next proof must be over a curve whose scalar field equals the base field of the previous curve.

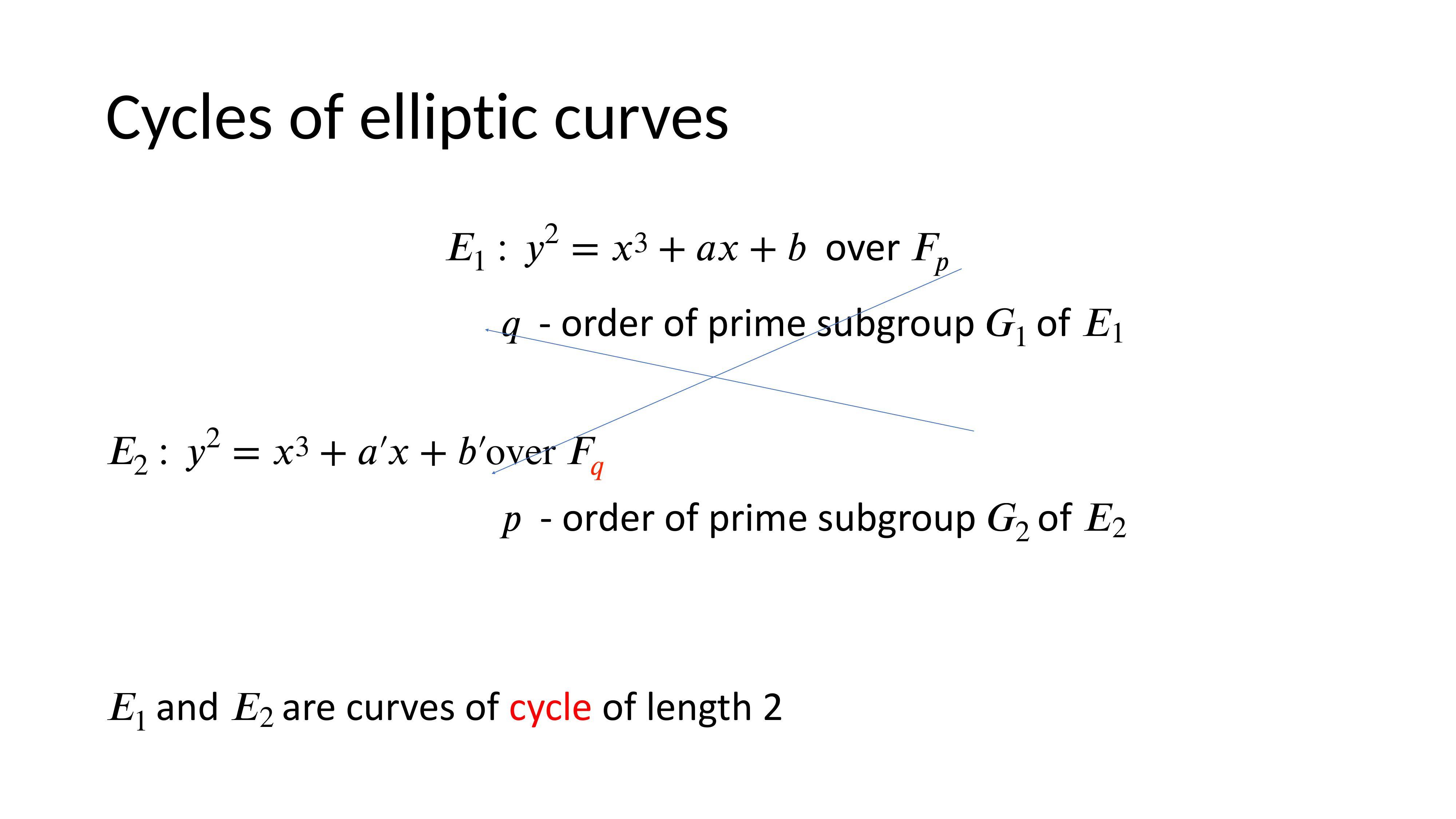

Cycles of Elliptic Curves

Curve cycles allow breaking large computations into chunks, proving in one field, then another, and cycling back. However, anomalous curves (where the scalar field equals the base field) cannot be used in cryptography due to vulnerability to fast discrete logarithm attacks.

Some Cyclic Pairing-Friendly Curves

Examples like MNT4 and MNT6 exist and are well-documented, but using them reduces performance by ~10× due to their much larger field sizes.

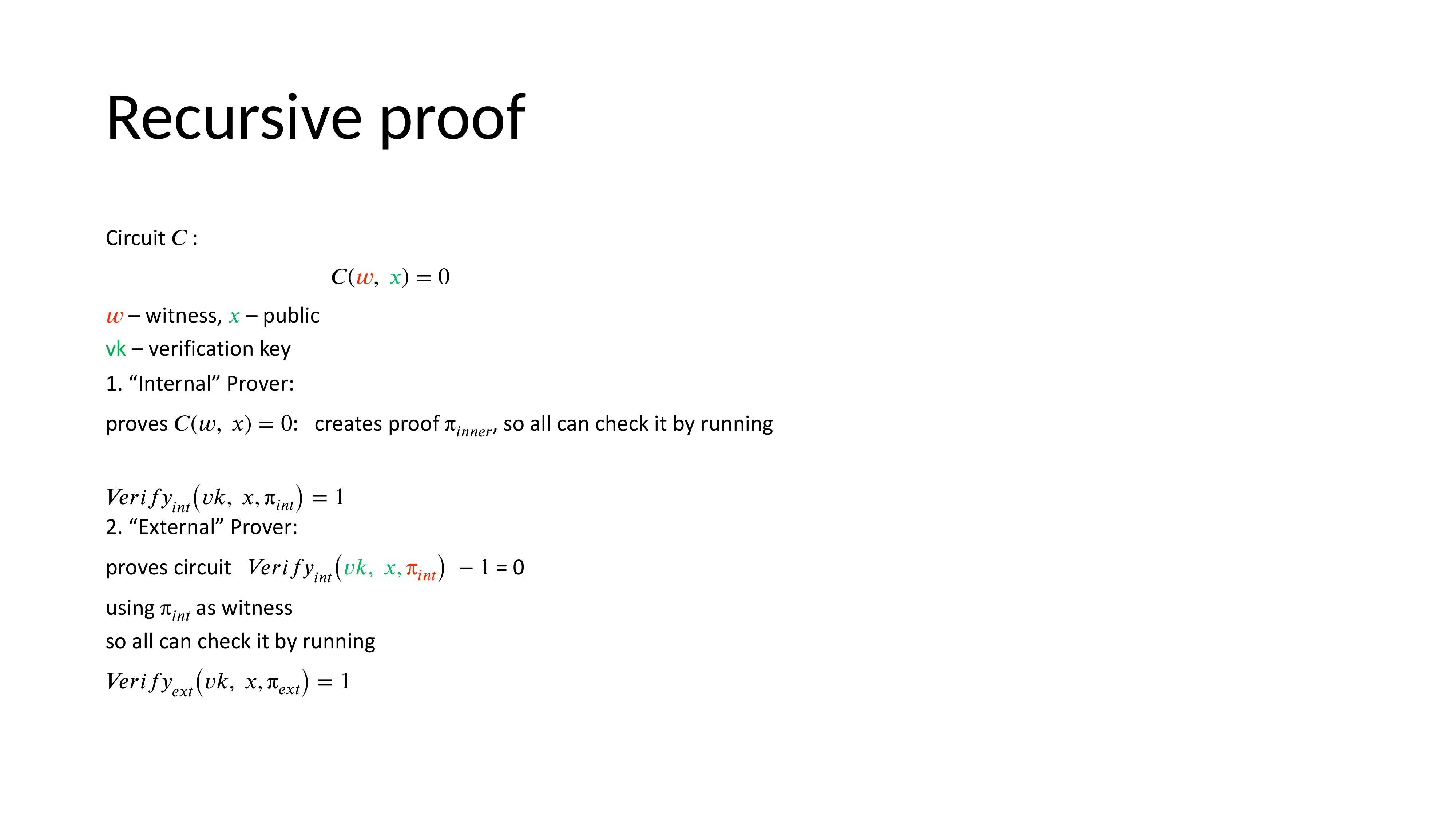

Recursive Proofs

A recursive proof verifies a proof of another circuit. The outer proof confirms that the inner proof’s verification logic was executed correctly, ensuring the original witness is valid.

Use Cases for SNARK Recursion

Recursion compresses complex proofs and is essential for zkRollups. For example, transaction batches can be proven in parallel (e.g., 10 transactions per proof), then recursively verified to produce a single compact proof. Merkle trees are typically used for parallelization.

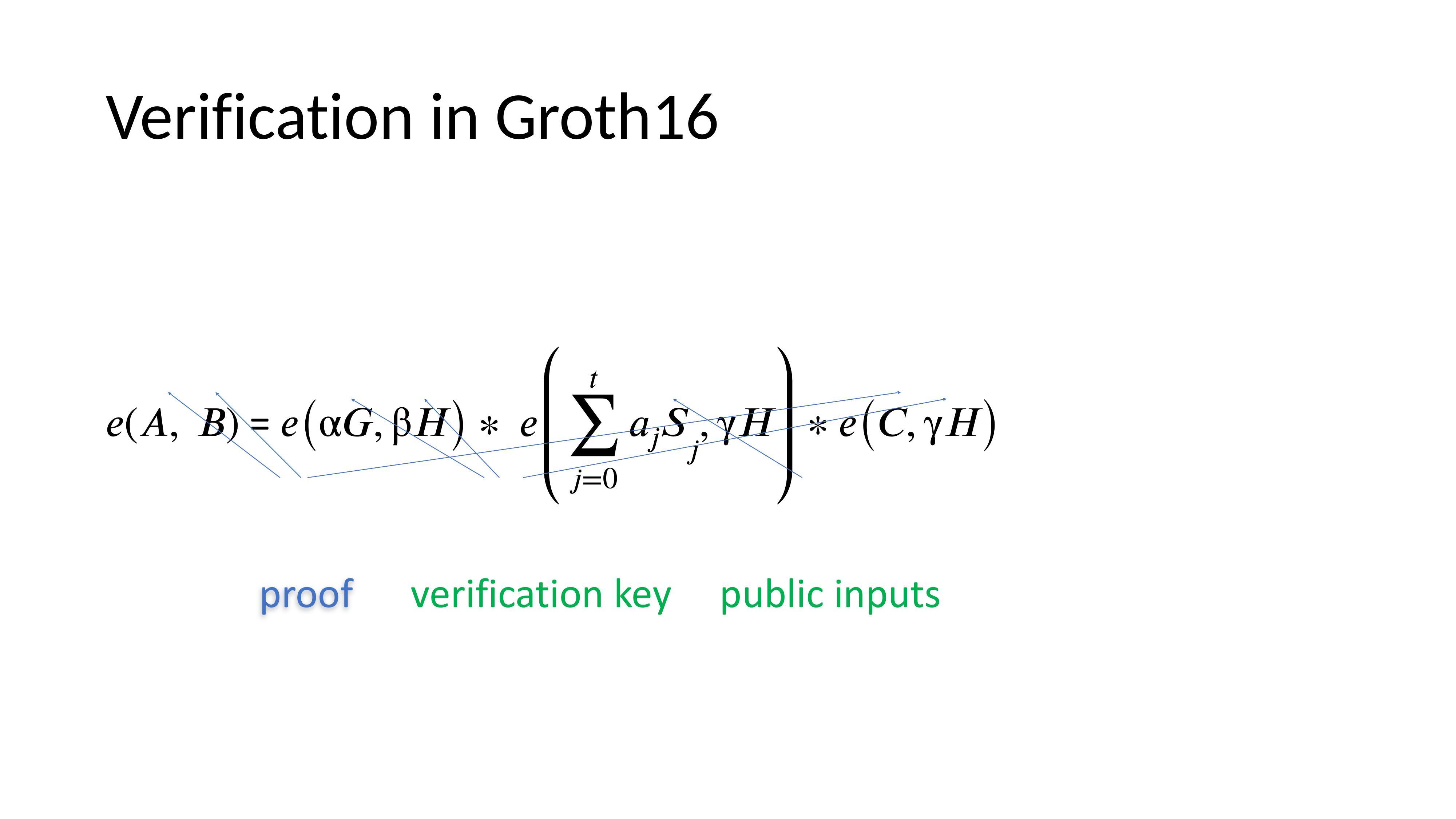

Verification in Groth16

Proving Groth16 verification directly requires huge constraint counts (~20M) due to multiple pairings, as there are no efficient pairing-friendly curve cycles. This bit-level proofing is slow; proving directly in the base field would be faster.

Plonk

KZG commitments in Plonk use pairing-friendly curves, leading to the same recursion issues as Groth16. Modified versions like Plonk2 replace KZG with lighter schemes such as FRI or Inner Product Argument.

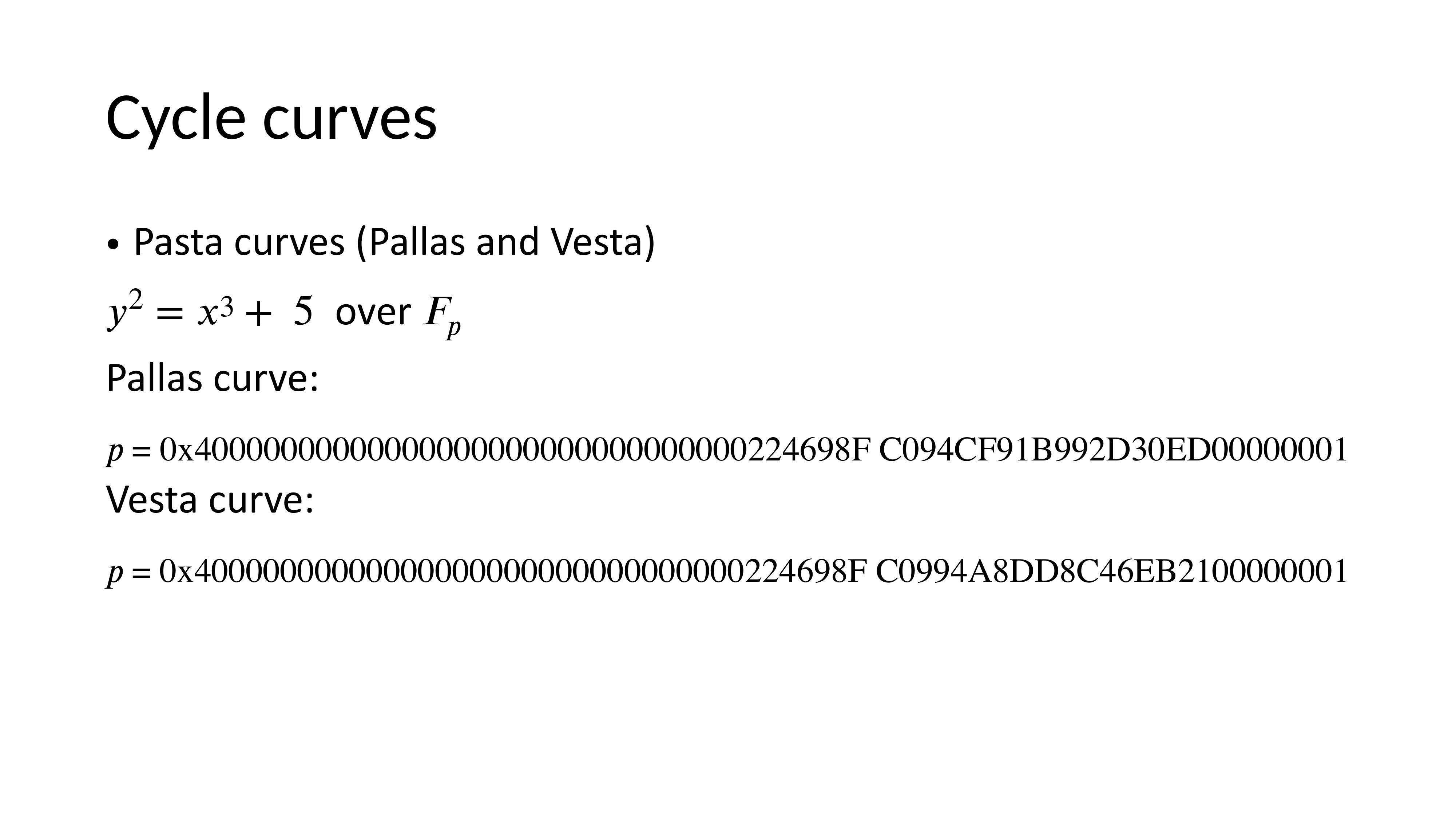

Cycle Curves

FRI does not use elliptic curves, and Inner Product Argument can use regular curves like Pallas and Vesta (the Pasta family), forming a cycle and avoiding bit-level proofs.

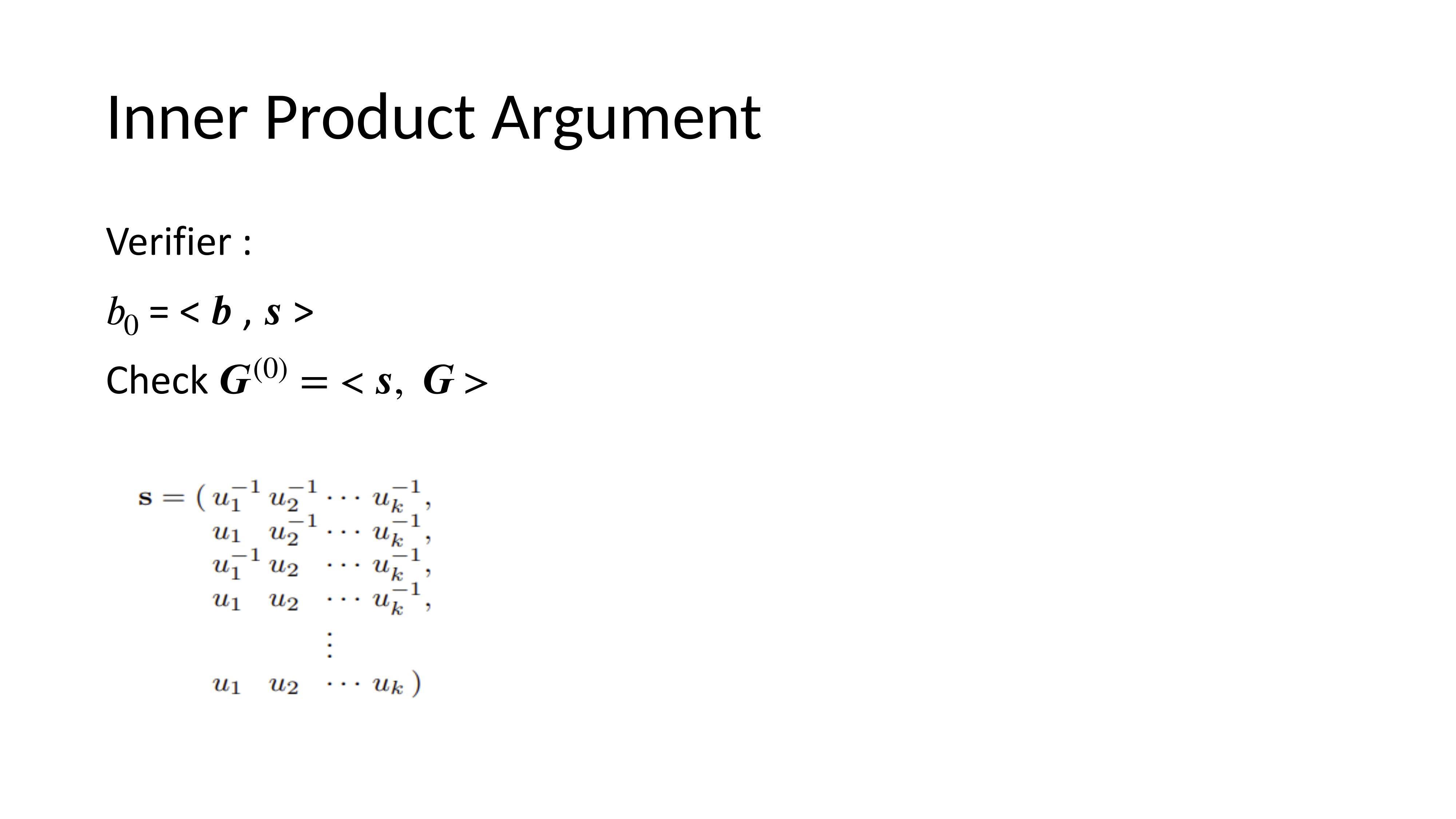

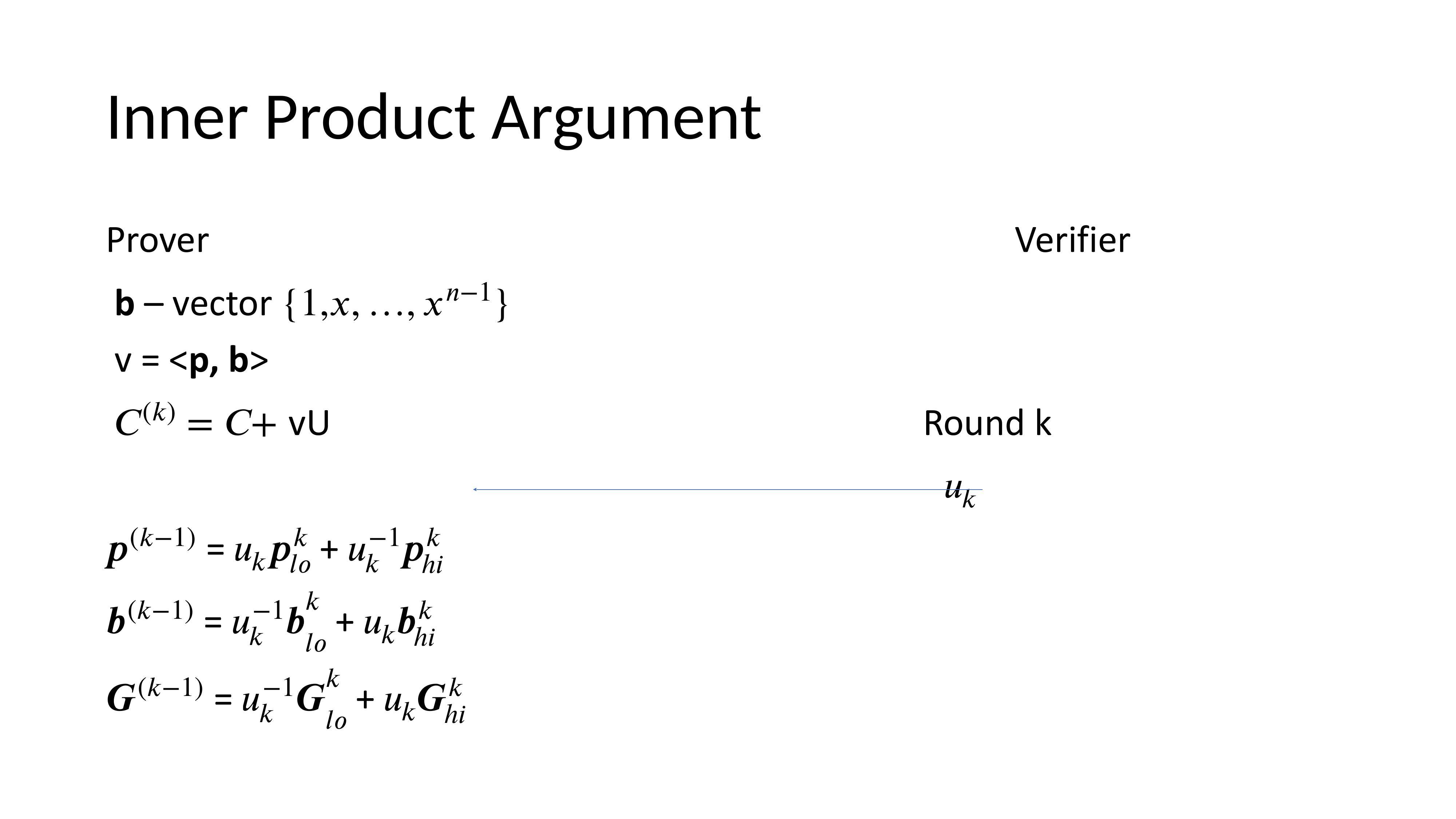

Inner Product Argument

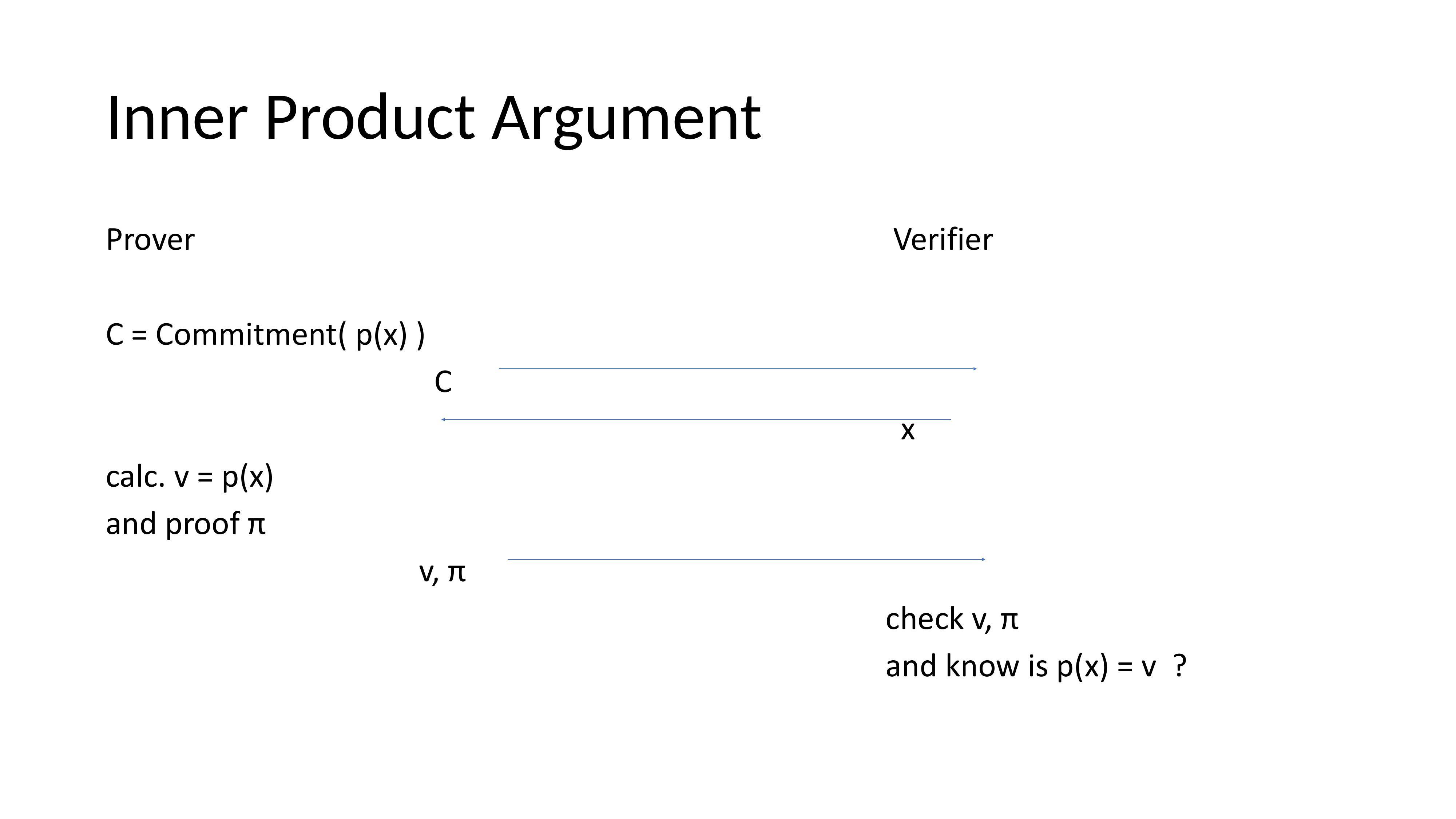

A polynomial commitment allows a prover to commit to a polynomial p(x) and later prove correct evaluation at a challenge point x without revealing the polynomial. This is done interactively between prover and verifier.

Pedersen Commitment

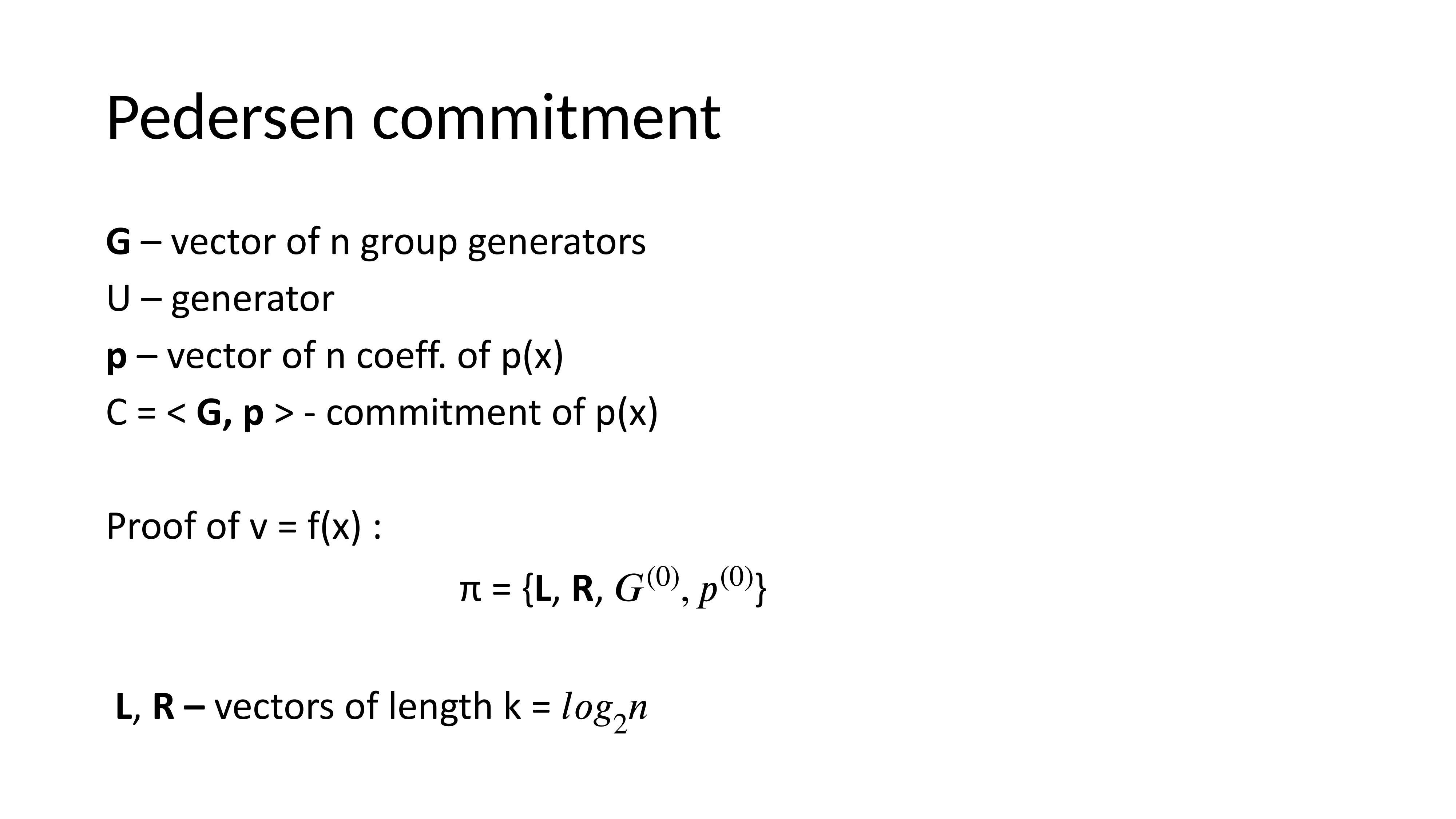

Given a vector of generators G and another generator U, commitments are secure if the discrete log between G elements and U is unknown. This allows proof sizes logarithmic in n.

Inner Product Argument Process

The commitment represents evaluating the polynomial. In each of k = log₂(n) rounds, vectors are split in half, challenges applied, and recombined until the verifier can check correctness.

Even with logarithmic proof size, the time complexity is linear. Recursion with accumulators allows batching verifications for better efficiency.